Due to self-determination, states have the right to define citizenship within their borders. A person who has no recognised nationality or citizenship is regarded as stateless. Gender inequality, which has undermined women´s dignity and equal status as citizens mostly in Middle Eastern and North African states, has made it difficult and sometimes impossible for women to pass on their nationality to their children. In the case of Lebanon, the inability for women to transfer their citizenship has far-reaching consequences that may result in stateless children.

Only three years ago, just 100 States adhered to the United Nation’s two statelessness treaties: the 1954 UN Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons and the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. As of today, critical mass on this issue is nearly attainable as the total number of accessions has risen to 144. However, 27 countries, including Lebanon, deny mothers the ability to pass on their citizenship to their children and to a foreign-born husband. Under the current Lebanese law, children can only receive citizenship through their father. Consequently, marriage to a foreign husband and children born to a Lebanese mother and foreign father would not be registered under the Lebanese government.

Today, approximately 76, 000 women are married to non-Lebanese men, making their children foreigners in their own country. As a result, these children are disenfranchised. They are barred from residency permits to remain in their own  country, prohibited from working unless they apply for work permits, and are unable to access fundamental government services such as public education and health care.

country, prohibited from working unless they apply for work permits, and are unable to access fundamental government services such as public education and health care.

Battling for citizenship rights, many have attempted to send proposals for new naturalization laws to the Lebanese parliament, but, not only were they never approved, the parliament said they did not receive them . While justifying unfair citizenship laws, the Lebanese government claims that excluding matrilineal citizenship and other jus sanguinis naturalization rights avoids possible sectarian imbalance. This widespread fear of naturalising children and spouses not purely of Lebanese descent, particularly of Palestinian descent, exposes the blatant discriminatory ethos of Lebanese politicians. This is because the government fears multiculturalism and as a result bars greater citizenship rights. The government and others who are against liberalizing citizenship rights argue that by introducing new ethnic minorities to Lebanon may aggravate pre-existing tensions among Lebanese Shias, Sunnis, and Christians. They conclude that granting naturalization to more individuals will lead to an increasingly unstable government and economy that is already pressured.

Today, around 200, 000 men, women, and children, mostly of Palestinian origin, are stateless, although a female family member is Lebanese. The United Nations Refugee Agency considers Lebanon as one of the seven worst countries when it comes to safeguards against statelessness.

Although, to most individuals and governments, citizenship, just like DNA, is a matter of heritage and is something a parent passes to a child without thought or effort. However, every one in seven countries has laws or policies prohibiting or limiting the rights of women to pass citizenship to a child or non-citizen spouse. The U.N. tracks these laws as a part of its work to monitor stateless populations, and particularly children who may become stateless if they cannot acquire nationality from either parent.

The U.N. assumes that citizenship is a basic right for everyone since it is proof of existence and guarantees basic rights to civil, political, and social engagement.

Almost exactly a year ago, in an attempt to end statelessness around the globe, the United Nations launched the UNHCR #IBELONG Campaign to End Statelessness by 2024 and it aims to make citizenship a fundamental right by shining light on this issue to encourage states to reform their naturalization laws.

Most victims of statelessness in Lebanon and the rest of the world are children that are faced with a challenging future in the country where they were born. The #IBELONG campaign created an Open Letter, a 10-point Global Action Plan to End Statelessness by 2024, and a petition that has signatories calling for states like Lebanon to rectify this dire situation. But where are we almost exactly a year after the #IBelong Campaign was launched on November 4, 2014? Citizenship rights are  still denied and more individuals are categorized as stateless, with no state to belong to. Moreover, approximately 10 million individuals are stateless around the world and the number escalates as a baby is born stateless every 10 minutes. Although there are more states in adherence to the two United Nations’ statelessness treaties than ever before, progress is glacial.

still denied and more individuals are categorized as stateless, with no state to belong to. Moreover, approximately 10 million individuals are stateless around the world and the number escalates as a baby is born stateless every 10 minutes. Although there are more states in adherence to the two United Nations’ statelessness treaties than ever before, progress is glacial.

Lebanon denies women´s rights to transfer her citizenship, but, at the same time, claims to be the most liberalised country in the Middle East. Among others, rampant ethnic tensions and a refugee crisis, the Lebanese government has to balance many issues, but it does not work in their favour to forget about women’s rights and deny them the right to pass on their citizenship to their children and spouses. As the UNHCR Open Letter states: “Ending statelessness would right these terrible wrongs. But it would also strengthen society in countries where stateless people are found, by making it possible to draw on their energy and talents. It is both an obligation and an opportunity for governments everywhere to put an end to this exclusion.” Time will only tell if by 2024 the UNHCR and #IBelong Campaign end statelessness for good.

By Pamela Tannous

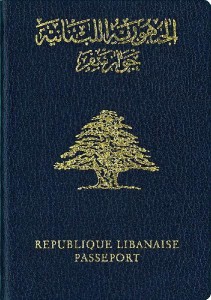

Image Credit:

Picture 1: A.h. king licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0