Night falls fast in the Land of the Incorruptible. The quietude that covers Burkina Faso’s capital, Ouagadougou, and the gloriously starlit West African sky stretching from horizon to horizon contradict the turmoil of the country. Burkina Faso is among the poorest in the world according to the Human Development Index, the literacy rate is the second lowest in the world, and almost half of the country lives below the poverty level. Public dissatisfaction culminated in a revolution in October 2014, sweeping President Blaise Campaoré out of office after 27 years. The country appeared to be on the way to democracy, following the example of the young reformer who ruled the country 30 years ago: Thomas Sankara.

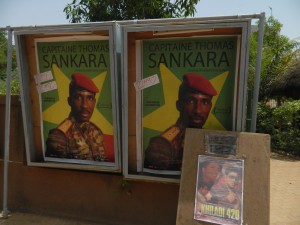

One night while in Burkina Faso, I decide to go to one of the many cinemas in “Africa’s movie capital.” My new friend Jacky, who sells T-shirts of Thomas Sankara on the streets of Ouagadougou, joins me. This summer, all of the cinemas show the same movie: “Capitaine Thomas Sankara.”

By the time we arrive at “Cine Neerwaya” it is midnight and the last screening of the day is about to start. A beamer buzzes quietly in the middle of the room, a tired operator materialises out of the gloomy shade in the back of the auditorium and inserts the disk. Suddenly, a charismatic voice fills the auditorium: “While revolutionaries as individuals can be murdered, you cannot kill ideas!” The voice is belonging to, of course, Thomas Sankara.

The young president, nicknamed “Africa’s Ché Guevara,” governed Burkina Faso in the 1980s. Not only did Sankara give the country the name it carries to this day – Burkina Faso, The Land of The Incorruptible – he also fought for women’s rights, against desertification and other environmental issues, criticised France’s former president, François Mitterrand, for the imperialist role former colonist countries on the world stage, and tried to break the country’s dependence on  foreign aid, claiming “the hand that feeds you controls you” and forbade forced marriage and female genital mutilation. Also, he declared a dream of his: to see Burkinabe astronauts trained in an African space program that could compete with Soviet plans. Lastly, within two years, he doubled the amount of children going to school through a education reforms. On the 15th of October 1987 Thomas Sankara was assassinated by Blaise Campaoré, prematurely ending Burkina Faso’s positive evolution.

foreign aid, claiming “the hand that feeds you controls you” and forbade forced marriage and female genital mutilation. Also, he declared a dream of his: to see Burkinabe astronauts trained in an African space program that could compete with Soviet plans. Lastly, within two years, he doubled the amount of children going to school through a education reforms. On the 15th of October 1987 Thomas Sankara was assassinated by Blaise Campaoré, prematurely ending Burkina Faso’s positive evolution.

When Sankara died his property consisted of a house that was yet to be paid for, $350 USD in his bank account, several bikes and two guitars. Testimony of a lifestyle that was in stark contrast to many African leaders then and now. His lifestyle as well as his political agenda made him suspicious to international organisations, such as the World Bank, and Burkinabe feudal lords who he had previously disowned. Campaoré made sure not to repeat the mistakes of his predecessor and started to privatise what Sankara had nationalised. As opposed to Sankara’s regime Campaoré’s government relied on oligarchical and dictatorial governance as well as several international allies who had disregarded Burkina Faso during Sankara’s regime. Campaoré distinguished himself as a corrupt leader who favoured nepotism although he was a valued ally internationally because of Burkina Faso’s rich resources.

Now when I stroll the dusty streets of Ouagadougou, 27 years after the coup d’état that murdered Burkina Faso’s visionary, Sankara, I come upon news stands on every street corner. Crowds of people gather in front of these to catch the latest scandals about Campaoré: corruption, depletion of the country’s resources, and murders of outspoken journalists. Burkinabe civilians tag the walls of their hometown with “Justice pour Sankara”, and “Justice pour notre morts” – Justice for Sankara and Justice for our dead. What has happened?

In late 2013 Campaoré, who was still president, tried to initiate a constitutional amendment to extend his term limits. The opposition organized protests and the people assembled on the streets. During the last weeks of October 2014, days before the amendment was called to vote, Burkina Faso saw the biggest demonstration in its nation’s history. Protestors demanded, as Sankara once demanded, : “La patrie où la mort!” – The fatherland or death. Bowing to public pressure Campaoré resigned. A transitional government was initiated and headed by the military leader Yakouba Zida. Along with transitional President Michel Kafando, Prime Minister Zida was commissioned to organise free and fair democratic elections. The rule of one of Africa’s last “big men” of the likes of Mobutu, Eyadema or Omar Bongo ended.

The summer after the revolution is a summer of hope and anxiety. Wherever I go, whoever I ask, I always get similar answers: the elections will be a step forward for the country, but the move towards democracy is a perilous one. Pierre, who used to be involved with a gold mining venture in Tiébélé, which is close to the Ghanaian boarder, now runs a small hostel. He says Burkina Faso should take precautionary measures to not replicate the devolution of the Arab Spring. The ongoing civil war in Mali, their northern neighbour and the growing extremism in West Africa with “Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb” in the north and “Boko Haram” in the east of Burkina Faso, create an unstable and hostile environment for democratization to take root, Pierre warns.

Most Burkinabe are, however, proud and confident when they talk about the revolution. They talk about unity, prosperity, democracy. Hopes are up, and so the spirit of Thomas Sankara lives on.

Four months later. Almost one year has passed since Campaoré resigned. 11th of October 2015. The day the people of Burkina Faso, the Bobo and the Dioula, the Mossi and the Lobi and all the other peoples in the country, have been looking for over the past year. The day that incited so much hope, so much optimism, and so much tension. The day of elections has come. But the situation has changed.

A month before the election, the Régiment de sécurité présidentiel, an elite troupe commissioned to protect the president, under Campaorés associate  General Diendéré Gilbert, bursts into a cabinet meeting and arrests the transitional government. Diendéré announces elections came too early for the country. The beacon of hope the revolution has become for African countries in the grip of rulers unwilling to give up power, from Rwanda to Congo Republic, seems extinguished.

General Diendéré Gilbert, bursts into a cabinet meeting and arrests the transitional government. Diendéré announces elections came too early for the country. The beacon of hope the revolution has become for African countries in the grip of rulers unwilling to give up power, from Rwanda to Congo Republic, seems extinguished.

Burkinabe have now taken to the streets once again. In Bobo–Dioulasso, the country’s second largest city, a crowd of women marched to demand President Kafando’s release. In Ouagadougou, once more stones flew against the seat of government. But this time, the protesters have strong allies from Washington D.C. to Paris. A delegation of African governments have called for a mediation. A tentative peace agreement has been made between Diendéré and Kafando which raises hope that elections may be rescheduled for the 22nd of November. While the situation in Burkina Faso remains uncertain, hope is spreading once more. But with hope here are no promises.

Yet confidence is fitting. As I pass the throng of Burkinabe after the movie I see dedication and an unshakeable will for democracy. Sankara may not be here to lead them, but whatever may happen this November, the people have learned one thing: “While revolutionaries as individuals can be murdered, you cannot kill ideas!”

By Paul Hattig

Image Credit:

Picture 1&2: Paul Hattig