“In those histories, half tradition,

With their mythic thread of gold,

We shall find the name and story

Of thy cities fair and old.

[—]

Every heart has such a country,

Some Atlantis loved and lost;

Where upon the gleaming sand-bars

Once life’s fitful ocean tossed.

[—]

Now above this lost Atlantis

Roll the restless seas of Time.”

The Lost Atlantis, Edith Willis Linn Forbes

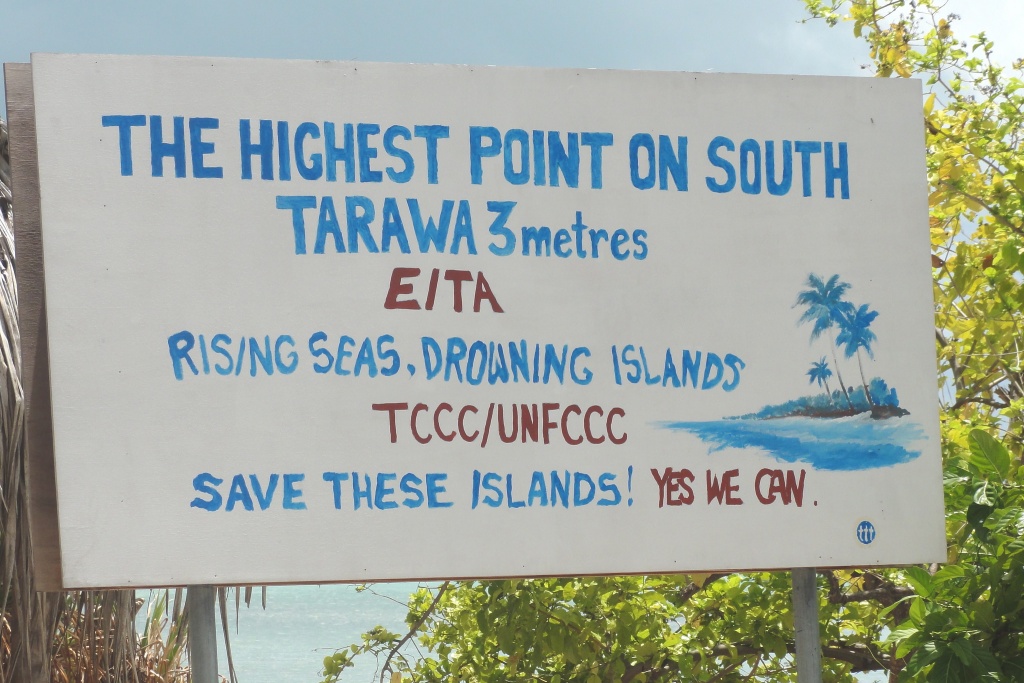

The impacts of climate change are revealing themselves at a varying pace around the world. The inevitable changes in the world the way we have known it will produce a multitude of responses amongst nations. We are witnessing the shaping of a new world order very different to what we have imagined. In this article I will examine the case of climate refugees in the context of the Pacific Islands, where low-lying nations are forced to consider such seemingly far-fetched adaptation strategies as buying land on foreign soil in order to secure territory for the relocation of the population when their home islands will unavoidably submerge as sea levels continue to rise. The story unfolding is that of countries loved and lost, resembling the mythical tale of Atlantis. I will specifically look at the case of Kiribati and its climate evacuation plans.

Climate refugees

According to various security experts, the risks related to unchecked climate change include extreme risks to food security, elevated risk of terrorism as states fail, and unprecedented migration that would overwhelm international assistance, among other factors compromising human and national security. In accordance, climate change has been called the greatest security threat of the 21st century.

According to worst-case scenarios, over 200 million people could easily become displaced by climate change. Numerically and geographically, South and East Asia, including the Pacific small island states are particularly vulnerable to events leading to large-scale forced migration. This is because sea level rise will have a disproportionate effect on the vast masses living in low-lying areas.

This forced migration triggered by climate events would affect development negatively in various ways. There would be an increasing pressure on urban infrastructure and services, which would undermine economic growth and increase the risk of conflict. Forced migration would result in worsened health, educational and social indicators among climate migrants themselves.

The restless seas rolling over Kiribati

The Pacific Island nation of Kiribati is one of the first countries in danger of becoming completely uninhabitable due to climate change. Kiribati is composed of 33 atolls, which are ring-shaped coral reefs encircling a lagoon. Atolls are by nature low-lying, and have a high ratio of coastline to land area, which makes them extremely vulnerable to various problems related to climate change, such as sea-level rise, shore erosion, fresh water contamination and disastrous storm surges. Kiribati has already experienced some of its islets vanishing into the Pacific. In addition, Kiribati is threatened by the rising sea temperatures which forms a severe risk to the coral reefs sustaining the atolls and their islands.

There have been several other attempts at implementing adaptation strategies, at varying, often poor, degrees of success. These strategies have included the construction of sea walls and water management plants, as well as installing rainwater-harvesting systems. However, such measures are not financially realistic for resource-poor and aid-dependent countries like Kiribati. To implement a reliable climate adaptation strategy would require consistent, long-term funding for which development aid is insufficient.

Thus, the government of Kiribati has promoted the concept of “migration with dignity”, in which residents are guided towards the option of considering moving abroad if they are equipped with employable skills. The Kiribati government has in fact launched a programme called the Education for Migration programme intended to make the Kiribati population more attractive as immigrants by focusing on enforcing their skill sets. Another novel idea has surfaced in which international refugee law is applied for climate refugees who are forced from their homes due to the consequences of climate change.

The more radical step has been in preparation for an extreme humanitarian evacuation: Kiribati bought approximately 20 km2 of land in Fiji, as a potential refuge. Fiji’s higher elevation and more stable shoreline make it less vulnerable than the islands of Kiribati. The former president of Kiribati, Anote Tong, who was in charge of the Fiji purchase, intended it to be a signal for the rest of the world in the form of a cry for attention regarding the predicament the Pacific island states are in.

A lost Utopia or climate extinction?

As the effects of climate change are revealed, nations like Kiribati are forced to prepare for the ultimate fight for survival. According to scientists’ predictions a significant portion of Kiribati will be uninhabitable within only a few decades. The question is not merely about safely relocating the biomass of the nation – its population – but there should be an existential urgency regarding the preservation of their national identity, culture and traditions. As we continue this haphazard and blasé approach towards climate change, climate migration and climate evacuation, we are possibly turning a blind eye towards the dawning era of de facto human climate extinction regarding cultures and communities. In the case of Kiribati and the other low-lying Pacific island states, only time will show if the future generations of the Pacific will have mere wistful myths and a restless sea of time rolling over their beloved countries and nations.

Anna Bernard

Photo 1: 2012. Kiribati Grunge Flag by Nicolas Raymond, Attribution 3.0 Generic (CC BY 3.0);Photo 2: 2009. Millenium atoll by The TerraMar Project, Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0); Photo 3: 2011. As an extremely low-lying country, surrounded by vast oceans, Kiribati is at risk from the negative effects of climate change, such as sea-level rise and storm surges, by Erin Magee / DFAT, Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)