Social movements are inherently the result of their social context, and no movement serves a better example of this than feminism. On its surface, feminism may seem like a straightforward and self-contained social movement, but on closer examination it becomes clear that feminist movements can’t be separated from the historical context in which they developed. From the early opposition to slavery to modern anti-capitalism, most of the movements seeking to change the social order during the previous two centuries included women and women’s liberation in a crucial role.

In the mid-19th century United States, the feminist movement grew out of and was intertwined with the anti-slavery abolition movement. The activists of the 1800s saw parallel between the lack of rights experienced by slaves and those experienced by women. Male resistance to the political participation by women in abolitionist groups led them to carve out their own political spaces, as well as eventually focus entirely on the legal issues of women’s suffrage and legal equality. This characterizes the first wave of feminism as stemming from a wider push for social equality. Both the practical experience from the slavery abolition movement, as well as the idea that social change could be brought about through activism, were the key to making the early women’s rights campaigns a success.

In the mid-19th century United States, the feminist movement grew out of and was intertwined with the anti-slavery abolition movement. The activists of the 1800s saw parallel between the lack of rights experienced by slaves and those experienced by women. Male resistance to the political participation by women in abolitionist groups led them to carve out their own political spaces, as well as eventually focus entirely on the legal issues of women’s suffrage and legal equality. This characterizes the first wave of feminism as stemming from a wider push for social equality. Both the practical experience from the slavery abolition movement, as well as the idea that social change could be brought about through activism, were the key to making the early women’s rights campaigns a success.

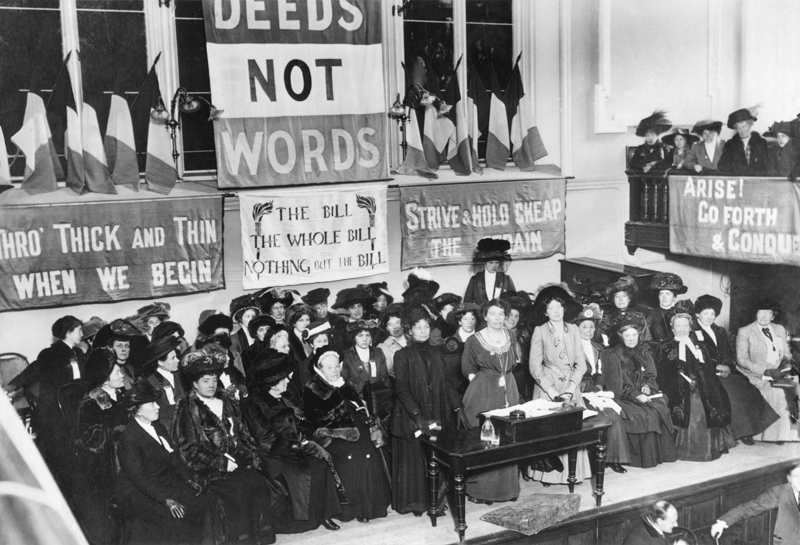

Women were also intimately involved with efforts to combat the social ills of industrialization on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. In the United Kingdom, women were one of the key constituencies of the radical Chartist movement, fighting for both democratic equality and social and economic justice. In the United States, the Progressive women of the early 20th century not only were involved in traditional feminist causes like suffrage and birth control access, but also wider social reforms like the minimum wage, the restriction on alcohol sales, and corporate corruption. To the female activists of the late 19th and early 20th century, the inequality between women and men was just a single facet of the larger social issues caused by the corrupt and decadent society they sought to reform.

One of the most radical social transformations of the 20th century was the Russian Revolution of 1917, which practically overnight transformed a traditional, religious and conservative Russia into an experiment in radical egalitarianism. Here, too, women and feminism could be found on the forefront of the social transformation. The new Soviet government immediately introduced a special department for women’s affairs – Department of Working Women and Peasant Women – led by women committed to gender equality. Under their purview, the Soviet Union became the first country in the world to fully legalize abortion, as well as introduced no-fault divorce, legal rights for out-of-wedlock children and child-support obligations for non-custodial fathers. However, even more radical was the participation of Soviet women in wartime activities. Approximately 66,000 Russian women fought in the Russian Civil War and as many as a million in World War II.

One of the most radical social transformations of the 20th century was the Russian Revolution of 1917, which practically overnight transformed a traditional, religious and conservative Russia into an experiment in radical egalitarianism. Here, too, women and feminism could be found on the forefront of the social transformation. The new Soviet government immediately introduced a special department for women’s affairs – Department of Working Women and Peasant Women – led by women committed to gender equality. Under their purview, the Soviet Union became the first country in the world to fully legalize abortion, as well as introduced no-fault divorce, legal rights for out-of-wedlock children and child-support obligations for non-custodial fathers. However, even more radical was the participation of Soviet women in wartime activities. Approximately 66,000 Russian women fought in the Russian Civil War and as many as a million in World War II.

The most famous of those was the 588th Night Bomber Regiment, which was an all-female unit that flew refurbished crop duster planes in night-time raids on German positions. They were so feared that the German troops called them Night Witches, while the German high command would award the highest military award to any soldier that shot one down. By comparison, many nations today are still just taking the first steps to gender equality in their militaries. In practice, women were not nearly as liberated as Soviet legislative efforts would suggest. Gender roles still played a significant role in what jobs men and women got, women were paid less for similar work and the economy and politics were still heavily male-dominated spheres. However, feminism still clearly played a major role in the Soviet leaders’ image of the new society they aimed to build and female empowerment was seen as simply another aspect of the grand social revolution.

Later in the 20th century and into the 21st, women’s movements would still be entangled with the social issues debated at the time. Women’s liberation in the 1960s and 1970s United States was linked to the protests against the Vietnam War and the growing civil rights movement before developing into its own independent movement. Today, feminist and gender equality concerns play a major role in the work of the World Social Forum, which seeks to address the fundamental inequalities in the world economy. Even the opposition to the recent election of Donald Trump as the President of the United States has been heavily driven by the feminist movement. It is impossible to separate out feminism from the general concerns about what is wrong with the world today.

Later in the 20th century and into the 21st, women’s movements would still be entangled with the social issues debated at the time. Women’s liberation in the 1960s and 1970s United States was linked to the protests against the Vietnam War and the growing civil rights movement before developing into its own independent movement. Today, feminist and gender equality concerns play a major role in the work of the World Social Forum, which seeks to address the fundamental inequalities in the world economy. Even the opposition to the recent election of Donald Trump as the President of the United States has been heavily driven by the feminist movement. It is impossible to separate out feminism from the general concerns about what is wrong with the world today.

For the last 200 years, and probably for as long as humanity has been around, we have been imagining ways to make the world a better place – more just, more equal, more prosperous and more peaceful. The history of feminism follows this history of utopian visions, from a world without slavery and drunkenness to a world without exploitation and nuclear weapons. As the social problems that need to be addressed change, so does the feminism that flows out of them. It is possible to look at feminism as simply being a movement about men and women, but in doing so one would be missing the great canvas of human struggle for a better world against which it is set. As long as there is a human society, there will be a drive for social change, and as long as there is the need for social change, there will be feminism.

By Yaroslav Mikhaylov

Image credits:

Cover Image: The New York Times Photo Archive, Public Domain

Image 1: Public Domain

Image 2: George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress), Public Domain

Image 3: Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army, Public Domain

Image 4: Alex Layzell, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic