It’s weird to imagine human beings as walking, talking sacs of water. After all, 70% of our body consists of it. Water is just as important to the individual as it is to the whole- it facilitates life on this planet. In 2010, the UN recognized water as a basic human right and called for countries and International Organizations to provide financial resources, help with capacity building and share technologies in order to grow together.

That’s fantastic right? Well, one thing studying political science teaches you is that it’s always complicated. Let’s try to break down the logistics of the idealistic goal of providing safe drinking water for the entire planet.

Water the tensions?

Fires require friction. And in this story, the friction is fundamental. Everyone needs water. However, clean water is scarce. How does one hydrate an exponentially growing population with the added complication of an imminent, irreversible, change of climate? Langford highlights that there are two dominant approaches to answer this question. The economic approach sees water as a commodity. This means that the delivery of water depends on market mechanisms and is regulated by price. Conversely, the social approach advocates for a top-priority universal access to water.

No prizes for guessing–the former is the dominant and widely practised approach.

In fact, several reports indicate that the implications of climate change would be droughts and mass water shortages. Researchers from the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre conducted a study wherein they identified areas in the world where the likelihood of a water war is more likely to occur. The most volatile of these areas are transboundary waters i.e water bodies that transcend political borders and are shared by neighbouring countries. The likelihood of water-related friction amongst these countries is expected to increase by 74.9 to 95 percent. The lead author of this study, Fabio Farinosi, said in a statement that the key factor that would equip countries to avoid conflict is cooperation.

And there’s the catch! Countries sharing rivers as part of their main fresh water supply find themselves in a zero sum game situation. Ideally, they need to balance domestic needs with the needs of every party involved. But the reality is far from this, as there exist a multitude of factors influencing a country’s stance on a foreign policy situation.

And the situation surrounding the world’s longest river is turning out to be quite the conundrum.

11 Recipes for War

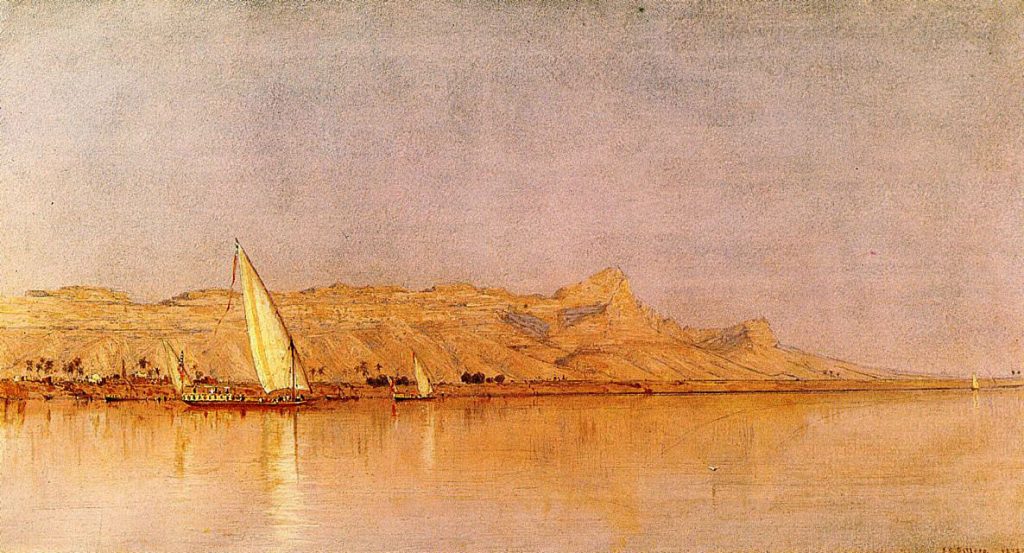

The Nile river basin encompasses 11 countries, and over 300 million people depend on it. Its resources, however, are distributed unequally and some countries are more vulnerable than others. In order to devise a win-win scenario, one needs to choose between equality and equity. Domestic and international needs must be shared instead of seen as a trade off.

Easier said than done. In particular, the geopolitical situation between Egypt and Ethiopia is quite concerning. The problem stems from the flow of river and the relative geography of the countries. For centuries, Egypt has had the lion’s share of the river, mainly due to historical treaties. It is also the most dependent on it. In 1979, the Egyptian president Anwar Sadat made the bold claim that the only thing that could make Egypt go to war is water. This status quo has been put to the test when Ethiopia decided on the creation of the largest dam in Africa by the blue Nile river.

How exactly is this a problem? Well, dams are like taps–they control the flow of the water. Moreover, Egypt happens to be at the bottom of this pyramid i.e. there are 10 other nations that are further upstream and would receive water from the Nile before Egypt. This concern was noted by Mohamed Abdel Aty–Egypt’s minister of water resources and irrigation. He estimates that if the water that’s coming to Egypt is reduced by 2% , one million people will be without a job.

From an Ethiopian perspective, the project to build the dam was seen as an initiative to fight their own poverty, and transition into a middle income country. Egypt’s claim to Nile’s waters can be traced back to the Nile Waters Agreement that was signed between Egypt and Sudan during the British colonial rule. This agreement assigned no water to Ethiopia and the other 8 countries that are based around the river. Thus, although Egypt might need the water most, the upstream states would not recognize its legal and historical claim.

The Ethiopian government claims that the dam would do no harm to Egypt because it is solely meant for hydroelectric purposes. The country has no plans to divert water for irrigation. This may be true in theory, but if the reservoir behind the dam is being filled, it could hold back water supply to Egypt for an entire year. This is especially worrisome for them because water passing through each upstream country comes with a unique set of complications. For instance, water passing through Ethiopian highlands would provide a year-long flow for Sudanese farmers that would be very pleased with this development. Alex de Waal of the World Peace Foundation states that the Sudanese government is already handing out leases for farmlands that will be irrigated once the dam in Ethiopia is built. While this is a boon for Sudan, it could be disastrous for Egypt.

Zero Sum Game

In addition to all the technicalities, there’s an emotional connection between Egyptians and the Nile. They’ve had an entire ancient civilization built around it. It’s their history- written in books and songs. If some sort of agreement isn’t reached, the chances for armed conflict are less abstract. It seems as though there’s trade offs to be made everywhere. One country’s misfortunes are another’s chance to grow and develop.

In such a stalemate, I’m reminded of the movie Saw–the one where a group of strangers play a sick game against their will that involves cutting off their own legs and other gory things for seven movies. It is later revealed that in every game, the strangers had to make a choice–similar to a zero sum situation wherein they either choose to win everything, or cooperate with each other. The idea was that in every situation, it was possible for every participant to survive through communication and trust.

This is the real world though. And unlike the Saw, the countries involved can get help from outside. If anything, the potential volatility in this region must be acknowledged by the African Union and the United Nations. War can always be prevented.

by Nikhil Gupta

Photo Credits:

On_The_Nile, pixelsniper CC BY 2.0

City of Aswan and the Nile river, Christian Junker CC BY NC NC 2.0

Nile Sudan, Stefan Gara CC BY NC ND

Nile at night, Bora S. Kamel CC BY NC SA