It is a challenge to find positive side-effects that a deadly global pandemic may bring to the world. With so much uncertainty, pain, fear, exhaustion, and death immediately surrounding us every day, the silver linings are hard to spot. Often, these silver linings turn out to be temporary: Healthcare workers that reaped applause from the balconies of this world several short months ago, are now expected to treat the organizers of anti-lockdown demonstrations with the same means as someone who has, for the last ten months, tuned down their personal whims in favour of a safer and more effective pandemic response. Those states that once delivered personal protection items and financial aid to less well-equipped parts of the world, are now hoarding vaccine doses that don’t even exist yet. How can you see the opportunities that an economic crisis might bring for the implementation of a promising European Green New Deal, if you have just lost your job and don’t know how long you can provide dinner for your family? How can you see some of the most effective responses to homelessness in years, while simultaneously so many people around the globe are pushed to their existential minimum, to the brink of losing their own homes?

The ones who cannot stay home

Upon giving out their first lockdown orders, many European governments quickly realized that to stay home, one must have a home to begin with. In one of their most rapid homelessness policy executions in years, the UK’s government ordered for almost 15,000 persons without permanent shelter to be relocated to empty hotel rooms, student dorms, and vacant housing. Similar governmental projects have been undertaken in France, Australia, and the U.S. In Germany, where coherent nation-wide policies on homelessness solutions not just during the corona pandemic are sparse and slow, non-governmental organizations have taken the lead when it comes to organizing hotel rooms for persons in need.

The message conveyed by a response such as the U.K.’s makes apparent how far policies to combat homelessness, provided they are backed up with sufficient funding, can come. Yet, it is also obvious—and so it has been for years for those engaged with this issue—that one emergency response upon another is not enough to overcome the issue once and for all. The urgency with which the matter has been addressed during times of crisis needs to become a new normal, if homelessness is to be confronted successfully.

Addressing homelessness is as complex as the diversity of the problem’s root causes. Among the main factors that push people on the street are stagnant wages and unemployment, matched with a lack of affordable housing and healthcare, discrimination, domestic violence and family problems.

4 Million people in the EU are homeless, 700,000 people sleeping rough every night—a figure that has increased by 70% in the last ten years alone. The disproportionate development of housing prices and inflation rates on the one hand and minimum income on the other put more and more individuals inside the EU in precarious situations. Over the past 10 years, the EU consumer price index (CPI) has increased by about 15%—inflation that remains unmatched by the increase in minimum wages, averaging 4.4% in the same time span. On top of this, housing costs in major European cities are skyrocketing: Rent has increased by 35% in Barcelona between 2010 and 2018, by over 50% in Paris between 2004 and 2019, and by over 70% in Berlin between 2004 and 2016.

Housing is becoming an especially disproportionate burden for low-income earners: In 2018, over one third of those households at the risk of poverty in the EU spent 40% of their income on housing. This makes livelihoods extremely prone to economic hardships—such as unemployment, furlough, or short-time allowance. U.K. authorities are gloomily predicting that “as many as half a million households could be at risk of homelessness once the full economic impact of the coronavirus is realized.” In other words: Mix unaffordable housing with a weakened economy, as we see it in times of the corona pandemic, give it a good stir and you have the perfect potion for a very real crisis.

The case of Vancouver provides a tragic example of the damage such an explosive cocktail of unaffordable housing and stagnant income can cause. The cut of governmental support for housing in the 1980s kicked loose a wave of homelessness that even caused the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (UNCESCR) to urge the Canadian government to declare the situation a national emergency. Within three years, between 2002 and 2005 the number of those without shelter in the Vancouver area nearly doubled, from 1,121 to 2,174. While the growth has been significantly slowed down since 2005, the trend has not yet been reversed and the most recent count in 2019 marked a peak of 2,223 people living on the streets of Vancouver.

In Canada, emergency responses, such as overnight shelters, have long been at the centre of homelessness management. While indispensable to addressing the issue, they are no sustainable solution to combat it in the long run. Unconditional access to permanent housing, known as the Housing First approach, has been identified as a key contributor to improve the situation of homeless people and communities in Vancouver. The Vancouver at Home (VAH) study, investigating a Housing First trial among homeless adults suffering from mental illnesses, has found that Housing First as compared to standard responses “produce significant benefits for participants, improve public safety and reduce the use of crisis and emergency resources.”

The City that Never Sleeps Rough

Similarly positive attitudes toward a readily accessible housing market are reflected by organizations around the world who stress that those provided with permanent shelter are more likely to seek help in other areas of their lives, too. One of the flag store implementations of the Housing First approach can be found in Finland: by investing over 250 million euros into affordable housing and support workers, the Finnish state, together with regional and non-governmental actors, has one of the most successful homelessness response mechanisms and prevention systems in the world. As a result, Finland is the only EU member state in which numbers of homeless are decreasing, with its capital Helsinki having virtually eradicated rough-sleeping.

While there are multiple success stories of individual cities’ and regions’ approach to homelessness—such as that of Trieste in Italy tackling homelessness by improving its mental health care system—the only lastingly effective approach is a systematic one. Only with common standards within a given state, or even beyond, can homelessness be eradicated once and for all. And what better way to create common standards than through common institutions? In a resolution from November 2020, the European Parliament urges the EU and its member states to end homelessness by 2030. While a detailed agenda is yet to be published, the Parliament recommends better access of homeless individuals to the labour market and healthcare, and a shift of focus from emergency responses to Housing First and prevention mechanisms. Concerning the latter, they recognize the pressing problem of unaffordable housing in European cities and announce a proposal to guarantee more inclusive housing markets. It might be just another policy proposal. But at least it is the long-overdue first step towards solving a problem that has been invisible, yet ever present on the horizon, for so many years.

In the summer of 2020, Barcelona cracked down on companies owning vacant apartments in the city by implementing a law that would allow the city to buy empty apartments at 50% of market values. In an unprecedented effort to create affordable housing, local authorities presented companies with an ultimatum of either renting out available apartments within a month or be subjected to compulsory sales at the described conditions. Paris, where as of 2017 over 26% of apartments are vacant, is imposing harsh fines on apartment owners breaking rules for Airbnb rentals, which “encourage property speculation and reduce the housing available to residents.” Berlin has implemented a temporary rent freeze for the year of 2021 and a permanent rent cap that regulates the allowed increase in rent in the following period.

The author Jonathan Safran Foer once wrote: “It’s always possible to wake someone from sleep, but no amount of noise will wake someone who is pretending to be asleep.” The pandemic has unleashed a crisis on so many different levels, producing so much noise that it becomes difficult to decide which problem to focus on first: healthcare professionals—to mention just those essential workers most immediately linked to the question of life and death—are ridiculously underpaid and undervalued, yet they remain equally taken for granted. Shutting down an entire economy, or at least having it run on low power mode to unburden healthcare workers, threatens the livelihoods of small businesses and their owners while feeding into the hands of enterprises. Limiting children’s right to education—while absolutely necessary when classrooms become a turnstile for a deadly virus—bears and exacerbates immense inequalities in opportunity. Living in a city and losing one’s job in the middle of all this very easily becomes an eviction notice. But all this noise, as overbearing as it might be, has also opened many eyes. We have to keep treating the invisible crises that the COVID-19 pandemic has brought to light with the urgency they deserve. We have to make sure that people can stay home. We must not go back to sleep.

Related articles:

Such a big world and still not enough space to live?

Photo credits:

By The Humantra on Unsplash

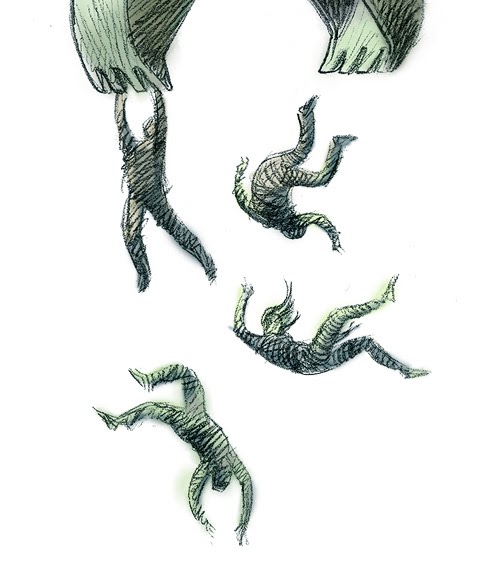

“On the scrapheap”, by Jon Berkeley on behance, CC BY-NC 4.0

“Balconies”, by unitednations on Unsplash