When my sister was living in Argentina a few years back, she, more than once, encountered the myth of the Nazi-Treasure. Does she know where to look? Does she know what exactly to look for? She is German, she must know something. And although South and Central America are known to be popular destinations of refuge for accused Nazi criminals, it turns out their treasure never made it over the big pond. In fact, it never even made it out of Germany.

In February 2012, German authorities made a spectacular discovery. What started out as an investigation for tax evasion against Cornelius Gurlitt, resulted in the finding of over 1,400 works of art that had disappeared over the course of the Nazi art theft. Although an official inventory was never published, the findings include pieces by renowned artists like Picasso, Monet, Liebermann, Matisse and Dürer. A minimum of 300 pieces were declared to belong to the body of Nazi “degenerated” art. The question is, how did this collection of Nazi stolen art art, worth hundreds of millions of dollars, end up in a small apartment in Munich?

An Expensive Ingenious Idea

It is commonly known that Adolf Hitler had a thing for art. Rejected as an artist by the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, he understood himself to be an unrecognized genius ruling both politics and culture with the power of a true artist. The notion of the genius and the Ingenious Idea, which Hitler largely adopted from philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, would become a major influencing factor on the Nazi’s disdain of modern art. According to Schopenhauer, the genius perceives an idea from the phenomenal world. Through technical skill he will manifest this idea into a piece of art and thereby help the ordinary person embrace the idea that is invisible to him normally. Vice versa, in Hitler’s opinion flawed and inferior ideas could also be worked into a painting or sculpture and consequently be internalized by the observer–something that would cause great harm to his perfect Aryan population.

What started out as an ideological move against any non-Aryan artistic idea soon turned into million dollar–or rather Reichsmark–business. Overall, Nazis stole an estimate of one-fifth of all artworks within Europe. Confiscated art, both from museums and private ownership, wasn’t only pilloried but sold to foreign buyers to finance war efforts, or traded for classical artworks Hitler desired for his planned Führermuseum. The business of stolen art caused a boom in the global art market, with artworks confiscated in Germany and German occupied countries ending up in museums and private hands all over Europe and North America.

What started out as an ideological move against any non-Aryan artistic idea soon turned into million dollar–or rather Reichsmark–business. Overall, Nazis stole an estimate of one-fifth of all artworks within Europe. Confiscated art, both from museums and private ownership, wasn’t only pilloried but sold to foreign buyers to finance war efforts, or traded for classical artworks Hitler desired for his planned Führermuseum. The business of stolen art caused a boom in the global art market, with artworks confiscated in Germany and German occupied countries ending up in museums and private hands all over Europe and North America.

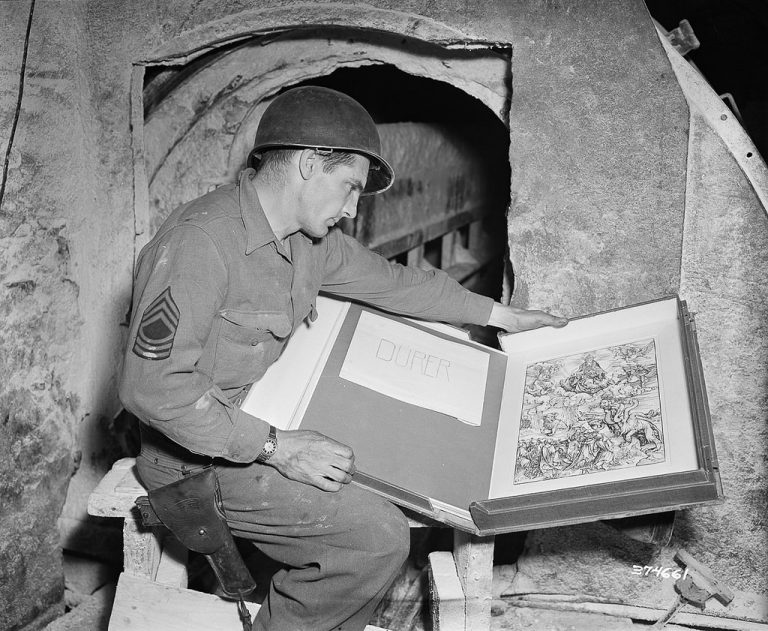

Monuments Men

The first big Nazi-Treasure was discovered right after the end of the Second World War by the Allied armies’ Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) Program, better known as the Monuments Men. The Altaussee salt mine in Austria contained over 12,500 stolen artworks, including 6,577 paintings, 230 sketches and watercolors, 954 illustrations, 173 statues, 1,200 cases of books and more. The MFAA, after a laborious recovery, soon began the long process of returning the stolen pieces of art to their rightful owners. And this is where the first problem arises–figuring out the rightful owner. Whereas the only appropriate thing to do–ethically and according to the ‘Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art’–was return the art to those it had been stolen from, things rarely happened that way. Buyers of stolen art, among them Hitler’s left hand Hermann Goering’s family, successfully claimed art confiscated from the family after the end of the war. Museums are often reluctant to give up pieces which have been claimed by their rightful owners. An example is the legal battle between the family of Paul von Mendelssohn-Bartholdy–a descendant from famous classical composer Felix Mendelssohn–and the state of Bavaria. At dispute is Picasso’s ‘Madame Soler’, with an estimated worth of $100 million.

The Burden of the Gurlitt Name

The 2012 Munich discovery hasn’t only revived the legal and historical issues around looted art but also the controversy around the Gurlitt family name. Hildebrand Gurlitt, Cornelius Gurlitt’s father, was one of the four art dealers in the Third Reich entrusted with the business of looted art. Being one-quarter Jewish and an aspiring young museum director with a liking for modern art, his relationship with the Nazis couldn’t be more complex. The chance to protect his family and save modern art from destruction by selling it abroad does not hide the fact that Gurlitt profited immensely from his deals, let alone that he knowingly dealt with stolen art. It’s difficult to pin him down as the good or the bad guy, and it is even more difficult to reappraise his deeds through his son, Cornelius. In an interview with him, German news magazine ‘Der Spiegel’ portray Cornelius as a man whose life “has become an infinite loop of remorse and coincidence”, a tragic figure bearing the consequences of his father’s actions. Whether Cornelius was aware of the full dimensions of his father’s business, remains questionable. What the interview does reveal is the intimate relationship of an 80-year-old man, “the heir of a collection with dubious origins”, with long-lost masterpieces of art. It is cases like these, which illustrate the difficulties that come with the restitution process, going far beyond legal issues. How can you ever truly make past injustices right and what if this involves an unjust procedure in the present?

An undeniably positive effect of the Gurlitt discovery is the attention and publicity it has drawn to the issue of stolen art. The Louvre has started to highlight works in their collection suspected of having been looted by the Nazis and then returned to France and the V&A Museum in London has invested in their provenance research. These little improvements initiated by individual museums, however, don’t release governments, above all the German, from facilitating the restitution process. Only if the government stuck to their obligations under the Washington Conference Principles and systematically identified looted art and encouraged pre-war owners to come forward and claim their property, could there be a chance of obliging museums to return objects of questionable nature to their rightful owners.

Even a domestic law in accordance to the Washington Conference Principles would not solve the problem of looted art as a whole. The Principles only apply to looted art in museums and do not concern private ownership, such as the case of Cornelius Gurlitt. So who knows how many more treasures of long-lost art are waiting to be discovered behind the plain doors of an ordinary apartment?

by Maya Diekmann

Photo Credits

IMG_0470A Pablo Picasso. 1881-1973, Jean Louis Mazieres, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Stolen Art, RV1864, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Stolen Art, RV1864, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Stolen Art, RV1864, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0