Since the 2010s, a sharp uptake in the levels of misinformation can be observed, in the push for so-called austerity, in the war on facts, in the bold attempts of different socio-political organizations to exchange fact for opinion.

The mechanisms of propaganda have mastered their most powerful array of tools yet––social media. That’s not to say misinformation hasn’t gone hand in hand with print media; it has walked hand in hand with factual information, since as long ago as the fifteenth century, when the printing press took off. In the intervening centuries, human society has, collectively, found ways to combat misinformation through methods of verification which, the hope was, the Internet would make foolproof. But rather than provide a higher standard, the rise of the Internet (and of social media, in particular) has seen the decline of hard journalism along with the printed press.

Nowadays, criticism is systematically dismissed as “fake news”––if not outright silenced––, no matter the source or topic it is aimed at. It would be easy to pin the blame on a name or on a score of them. Easy but misguided. The Trumps and Bolsaneros of the world are a symptom of an economic system at odds with itself, much like the ouroboros swallowing its own tail, at once hungry and suffering from agonising convulsions.

Marilynne Robinson, in a piece for the NYRB in June, “What Kind of Country Do We Want?” described this economic system as:

“…the snare in which humanity has been caught––great industry and commerce in service to great markets, with ethical restraint and respect for the distinctiveness of cultures…having fallen away in eager deference to profitability.This is not new, except for the way an unembarrassed opportunism has been enshrined among the laws of nature and has flourished destructively in the near absence of resistance or criticism.”

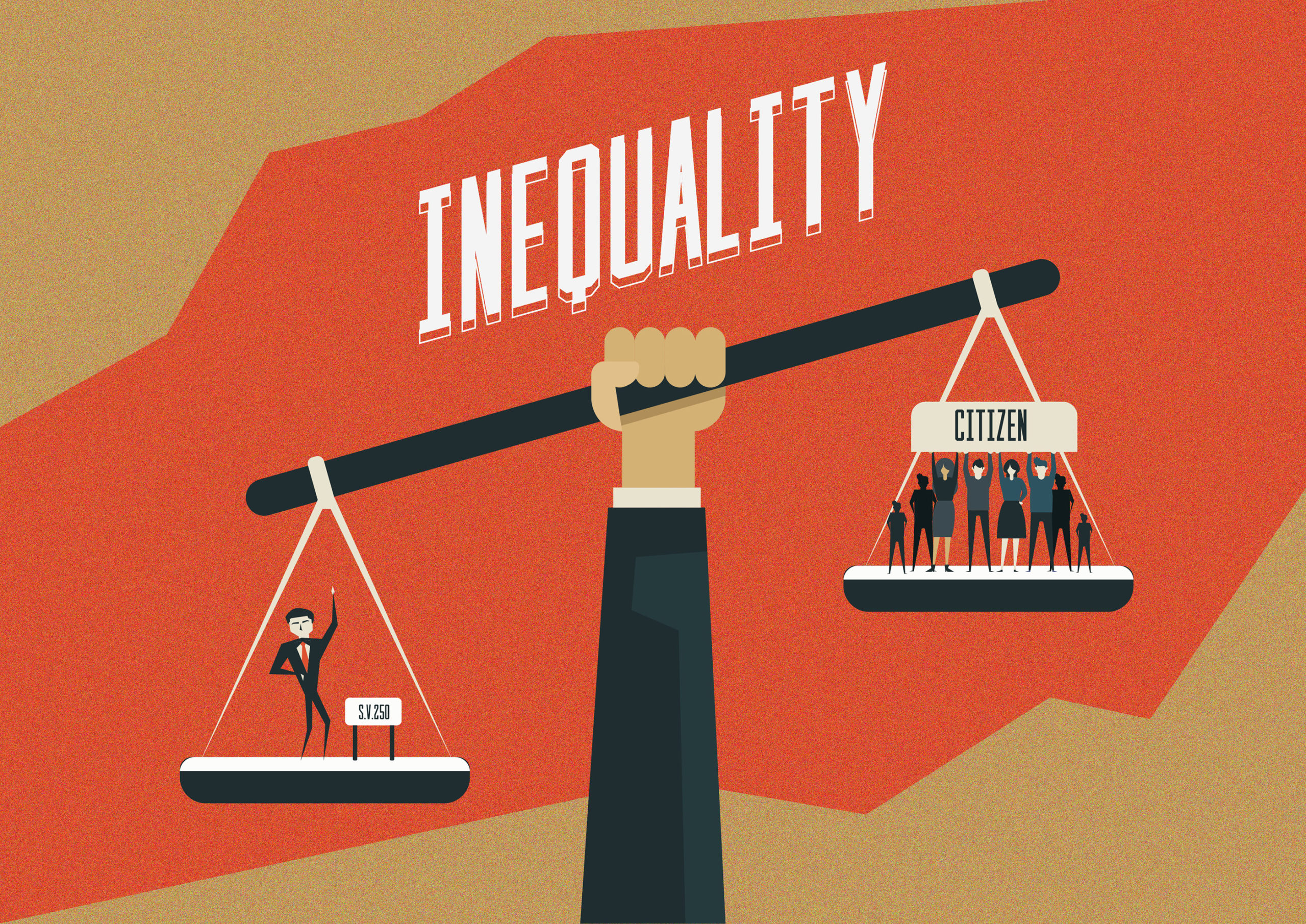

This is, Robinson writes, a “system now revealed as a tenuous set of arrangements that have been highly profitable for some people but gravely damaging to the world”. And not just the world––growing economic inequality is as high as it has ever been.

Inequality – A Cancer Eating Away at Society

Inequality affects “more than 70% of the global population,” according to a UN report, but nowhere is it more jarring, more on focus than in the richest, most powerful and prestigious countries in the world. To this end, it’s time to turn the reader’s attention to several recent developments, first in the USA and then in the UK.

Robinson describes the USA as “having been overtaken with a deep and general conviction of scarcity, a conviction that has become an expectation, then a kind of discipline, even an ethic. The sense of scarcity instantiates itself. It reinforces an anxiety that makes scarcity feel real and encroaching, and generosity, even investment, an imprudent risk.”

It is this sense of scarcity that drives society towards polarization, which Robinson in turn characterizes as “a virtual institutionalization in America of the ancient practice of denying working people the real or potential value of their work.” This institution couldn’t work without popular support. It is here that the mechanisms of branding––dare we call it by its non-politically correct name, propaganda?––enter into the scene. With them come their main beneficiaries, would-be demagogues whose interest lies in reinforcing the status quo.

Through the benefits of unified branding, large swathes of the population are persuaded to vote against their own interests. This branding rarely has a basis in fact, as is the case with perceptions of economic competence in the USA, for example. Every Republican administration from Reagan onward has overseen a recession, and every Democratic administration has overseen a strong recovery and an economic boom. Do Americans trust Democrats more to do a good job with the economy? On the contrary: the GOP enjoys a durable advantage, recently at eight points. The pandemic may agitate sentiments and approval numbers, but even in the chaotic era of President Trump, Americans irrationally trust in the GOP’s longstanding image as the party of practical, “fiscally conservative” businessmen who know how to run things efficiently and profitably. (Joseph O’Neill, “Brand New Dems?” for the NYRB)

This is no small feat of misinformation, but a wilful spread of what is equivalent to a mass delusion over decades. So, too, with migration; despite migrants performing jobs the vast majority of Americans do not want, their contribution to society is denied.

A Universal Problem

This is not a uniquely American issue, though the USA is perhaps the most extreme example––and the richest country in the world. If we turn to the UK, much the same can be seen, both in terms of a push for austerity and in the divorce from facts. For a decade now, British austerity has gutted the NHS (National Health Service)––in a time of a pandemic, the fault lines of this act couldn’t be more pronounced.

The “Leave” campaign was successful on the grounds of false claims, as well as racism and a perceived economic victimhood of the English (more so than any other group) at the hands of migrants. At the UK’s great economic loss over membership taxes to the EU, as well. Why is it, then, that British farmers were faced with the possibility of their harvest rotting, unpicked, on trees? This is an issue exacerbated by the coronavirus, certainly, but with its roots in the Eastern European migrant labour force that so offended English sensibilities, despite performing a job that no Britons are interested in.

And in February, Business Insider estimated that by the end of 2020, the British government will have spent £200 billion to leave the UK, more than all its payments to the Union over forty-seven years of membership. One cannot help but wonder what these funds might’ve accomplished, were they aimed at reducing economic inequality within the UK, rather than spent on a divorce bill.

What becomes clear through these examples––and many more like them––is that the drive towards ever greater profitability at the core of our economic system is not only flawed, it is a pandemic more deadly, more divisive than COVID-19 could ever be. Its tools seek to propagate an ideology of selfishness. And it is easy to drink its bitter message in. What’s required is only passive consent, a wilful lethargy, an unwillingness to look away from the screen.

Or… a different choice can be made. We can examine humanity through a prism not of its greed or rugged individualism, but through an outrage for the injustices embedded in our society, and most of all, through a shared human experience and selflessness.

Related articles:

The Social Network of Ethnic Conflict

Photo credits:

Astroturf by hanne jatho, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

INEQUALITY by Teeraphat Kansomngam, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Paul Harrop / Poster site, New Bridge Road, Newcastle / CC BY-SA 2.0