In the early 15th century, the Chinese admiral Zheng He sailed west from China, getting as far as the Arabian Peninsula and the east coast of Africa. It was one of the largest voyages of its kind during this time. Now, after six hundred years, China is once again following this trade route as it realises its newfound status as a major world power. Together with its efforts to revive the traditional Silk Road trading route, this constitutes China’s new One Belt, One Road trade and influence policy poised to directly challenge the global economic, military and cultural dominance of the Western world.

One Belt, One Road is a program of international agreements and infrastructure projects introduced by the Chinese President Xi Jinping in S eptember 2013 that is to culminate in the creation of two trade routes between China and Europe, Africa and beyond. One starts from Southern China and follows Admiral Zheng He’s sea route through Southeast Asia, India, Africa and the Red Sea, forming a maritime belt across the Eastern Hemisphere. The other is a land route going from the west of China through Central Asia, Iran, Turkey and Russia before reaching Europe, much in the same way as the Silk Road traders did since before the Roman Empire arose in the Italian Peninsula. On the face of it, it is merely a trade and infrastructure program designed to deliver China’s prodigal industrial output to the markets of Asia, Europe and Africa, but it is also designed to expand China’s influence across the hemisphere in a wide range of fields.

A key component of the One Belt, One Road program is the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), launched in June of last year. Its official goal is to provide loans for infrastructure development in Asian nations – especially the ones across the One Belt, One Road routes – in order to make it easier for Chinese goods to flow into and through those nations. However, it is also a direct competitor to the American- and European-dominated World Bank, offering “programs of development [that] will be open and inclusive, not exclusive. They will be a real chorus comprising all countries along the routes, not a solo for China itself” according to Xi Jinping. And just as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund became vessels for exporting Western policy preferences to the developed world, the AIIB is likely to also become a way for China to shape the international financial order more to its liking.

The One Belt, One Road project also seeks to export Chinese culture and a more Sino-centric view of world history. Silk Road-associated cultural sites are being promoted by pro-Chinese organisations across Central Asia and many have been nominated for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site status. A long-standing criticism of UNESCO is that its World Heritage Site list is very Eurocentric, so while inclusion of more Chinese or Chinese-influenced sites may make it more representative, it still demonstrates a shift in how we conceive of history – one that is far more favourable to China.

A large part of the One Belt, One Road plan consists of forging partnerships and creating institutions, but another big component of it is also acquisition of physical assets along the route. To help protect its shipping along the coast of Africa, China has begun constructing a large military base and harbour in Djibouti. This places China in a very exclusive club of nations that have military bases on more than one continent. And, according to China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi, this is only the start of China’s overseas military expansion. However, he has also insisted that China’s intentions are a peaceful “product of inclusive cooperation, not a tool of geopolitics, and must not be viewed with an outdated Cold War mentality”, though how China uses its newfound influence remains to be seen.

Chinese companies have also been expanding their control of shipping infrastructure across the globe. Some of their attempts were successful, such as the purchase of the Greek port of Piraeus by China Cosco Holdings. Others were less successful, such as a Chinese billionaire’s attempt to buy 300 square kilometres of Iceland, ostensibly for a golf resort though more likely for trade or military purposes. The offer was rejected by Iceland’s government as illegal under Icelandic law. Another failure was an attempt to build a canal between the Pacific and the Atlantic Oceans in Nicaragua that would have been twice as wide as the one running through Panama, but which was abandoned after its backer lost a significant portion of his wealth during a market downturn. Despite their failure, the projects’ scope and distance from China suggest the expanding global reach of Chinese investment capital.

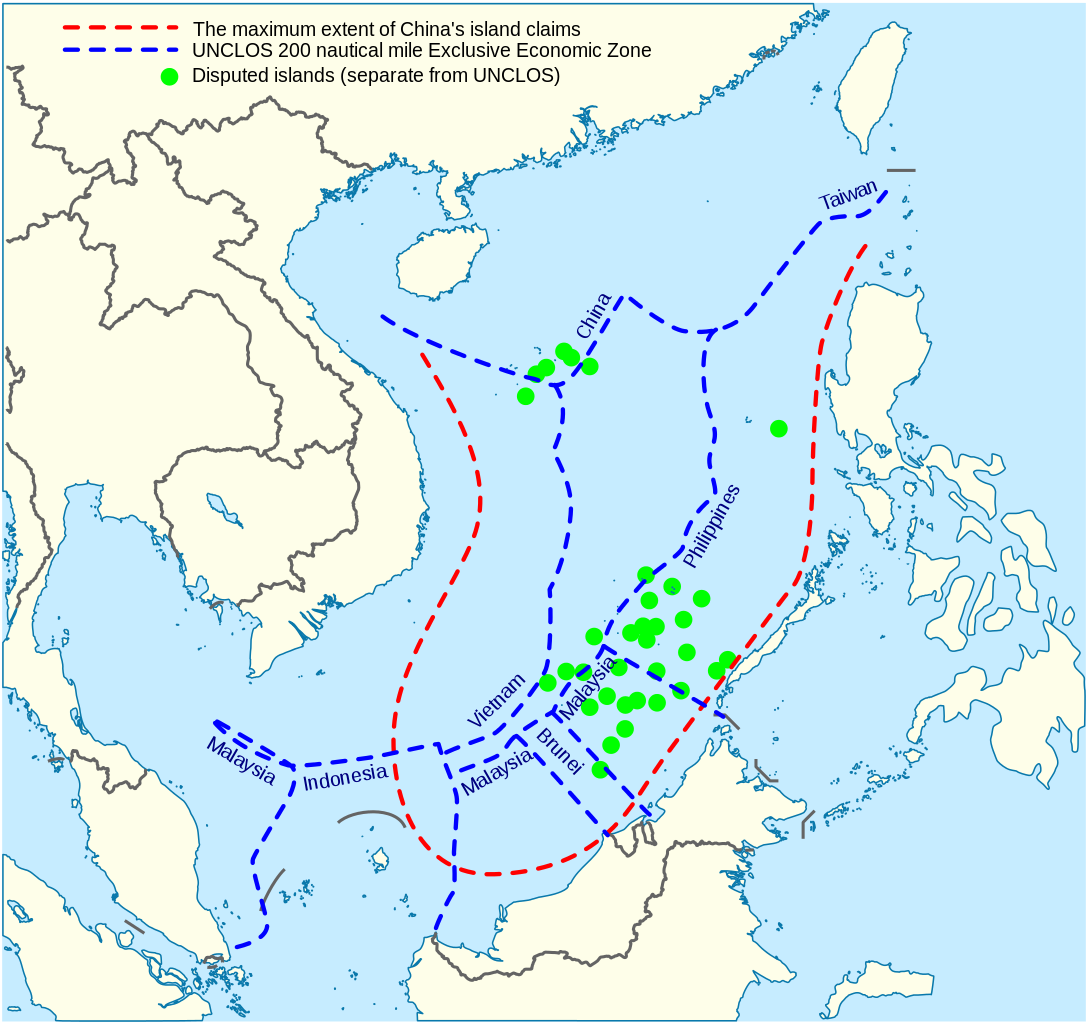

However, China’s road to global influence has been far from smooth. Much China coverage over the last year has been about the developing crisis in the South China Sea, where China claims control over naval territory that is also claimed by Vietnam, Malaysia, Philippines and Brunei, as well as the Republic of China – better known as Taiwan in the West. China has been supporting its claims by constructing artificial islands and deploying fighter planes and land-based rockets to them in an attempt to secure the region through military force. This has drawn opposition from the United States as hindering the freedom of navigation in the region, increasing tensions in the area even further. If this dispute is not resolved, it could severely undermine the sea-based half of the One Belt, One Road project.

China also faces significant international opposition to its plans, especially in Europe. Many European countries criticise China for its human rights violations, while China in turn publicly criticises nations that have hosted the Dalai Lama. He is a very popular figure in many Western nations, but China considers him a criminal for supporting the creation of an independent Tibet. Until these issues are resolved, they limit the extent to which increased economic integration with China is acceptable to European nations and the European public.

One Belt, One Road is an ambitious project that aims to change the nature of the global political, economic and social order to reflect the rising importance of China on the world stage. As part of this project, China builds new military bases, purchases infrastructure and even lobbies UN cultural bodies. In short, it is acting like a major world power. After many decades of relative political and economic isolation, One Belt, One Road represents a re-emergence of China into international affairs beyond its own back yard. If the One Belt, One Road project is successful, it will mark the beginning of a new era of international politics and if it is unsuccessful it will be a symbol of hubris of a want-to-be superpower. Either way, it will force a radical rethink of China’s standing among the world’s nations.

Image Credit:

Cover Photo: Chief Mass Communication Specialist David Rush for US Navy Pacific Fleet. Public Domain.

Picture 1: Splette, Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Picture 2: José Luis Filpo Cabana, Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY 3.0

Picture 3: Goran tek-en, Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY 3.0