“Eastern Europe is free. The Soviet Union itself is no more. This is a victory for democracy and freedom.” When US President George H. W. Bush, declared victory over the Soviet Union on December 26, 1991, after a Cold War that had nearly lasted half a century, he set the tone of what would become a given in Western understanding of history. The Soviet Union lost, communism lost, there is no longer any threat coming from the East. Just how wrong this framing of the end of the Cold War turned out to be, would slowly unveil itself over the years to come.

Of geopolitical disasters

Russia’s Vladimir Putin once called the dissolution of the Soviet Union “a major geopolitical disaster of the century.” What he referred to, was the fact that millions of ethnic Russians suddenly found themselves on foreign territory when the Union ceased to be in 1991. Time and time again this disaster turned out to be quite useful as an excuse for Russia to meddle with its neighbours’ politics. It even went so far as to inspire much of Putin’s speech to the Russian Federal Assembly that initiated the annexation of Crimea in 2014. No wonder that in other former members of the Soviet Union, where the integration of ethnic Russians has been rather draggish, fears of the big bad neighbour persist even almost thirty years after the Soviet Union disintegrated.

But would Russia really go as far as to annex a tiny peninsula home to roughly 1.5 million lands-people, despite being aware of the implications of such actions internationally? Of course not. The fact that Crimea’s inhabitants are mostly of Russian descent surely added a nice detail to the story, but ultimately Putin’s real asset on the peninsula were the deep, blue, and, most importantly, warm waters around it––the Russian naval base in Crimean Sevastopol, the only port that does not freeze over in the winter.

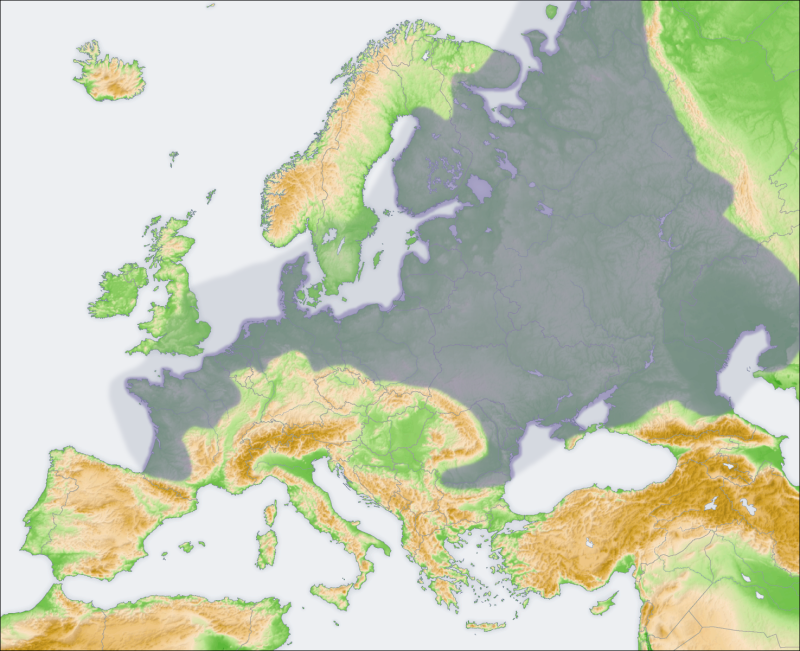

Which brings us to the real geopolitical disaster: Russia, like any other country in the world, is a slave to its own territory. There are some developments, which Russia is unlikely to ever accept. Losing the Ukraine would be one of them, and not just because of Sevastopol. Tim Marshall, author of the book “Prisoners of Geography,” writes that if Putin was the religious man he claims to be, he would pray for mountains in the Ukraine. Then, Russia wouldn’t have to worry about security threats from the West effortlessly cruising through the great corridor, the Northern European Plain, straight up to Moscow. Then, Russia wouldn’t have to worry about NATO at their doorstep.

Beware of NATO

And what a worry NATO is. Since its foundation, NATO has been a thorn in Russia’s (western) side. As an alliance created for the purpose of providing collective security against the Soviet Union, not even Mikhail Gorbachev, the ‘liberator’ of the East Bloc if you will, was particularly keen on having the pact’s forces anywhere near the Russian border. Moscow’s Council on Foreign and Defense Policy declared that NATO expansion would make “the Baltic states and Ukraine… a zone of intense strategic rivalries.”

Fast forward three decades and we have an armed conflict in the Donbass region of the Ukraine. This shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone who has actually listened to the Kremlin’s threats in the 1990s. The case of the Ukraine is a difficult and complex one and it combines the worst of both worlds of Russia’s problems: A big share of its population consists of ethnic Russians and it is of immense strategic importance to Russian territorial security. This makes it virtually impossible for Russia not to act when it sees the Ukraine flirting with the West. With over 3,000 casualties, and roughly 1.6 million displaced persons, the war in the Ukraine and, in particular, potential Russian involvement cannot and must not be justified. But it can be understood. And to understand, we cannot ignore the behaviour of the USA, Europe, and the historic West.

New peace, old fears

Perhaps after the end of the Cold War, one could have attempted what Germany and France managed after the Second World War. A similar mutual distrust, exacerbated by the lack of natural borders protecting against invaders, had kept Germany and France at odds in a similar fashion that Russia is at odds with Western Europe today.

But even if the NATO powers had wanted to, Russia simply could not have been integrated in the existing Atlantic security system after 1991. As Richard Sakwa writes: “In structural terms, Russia was too big, too independent, too proud and ultimately too strong to become part of an expanded ‘West’.” And instead of reforming existing structures and actively seeking cooperation and compromise with Russia, building the ‘Common European Home’ that Gorbachev had envisioned, the capitalist West saw itself to have won the day, leaving Russia with an unjustified sense of defeat, a questionable new ‘Cold Peace’, and old fears of the Great European Plain.

With its continuing “triumphalism”, the USA would go on to unilaterally influence international politics like no other, ultimately turning Russia away from Europe and the West. Sakwa describes 2003 as the year in which Putin decided that US involvement in the Iraq War demonstrated the nation’s true ambitions, its expansionist policies, which were incompatible with his embrace of national sovereignty––a firm position Russia has kept until this day. NATO’s and the EU’s expansion eastwards were a confirmation to Russia of what they were already suspecting. The West was coming for their neighbours, and ultimately, for them. And when the West reached Ukraine, Russia pulled the emergency brake.

Freedom in the Russian neighbourhood

Even as recently as 2014, the USA remains convinced that Ukraine can be anything but Russia’s neighbour. “[T]he future of Ukraine must be decided by the people of Ukraine”, were US President Barack Obama’s words before unleashing sanctions on Russia which, together with those of the EU, nearly “brought the Kremlin to its knees.” But Russia has adapted to the sanctions and proved surprisingly resilient to the external pressure. Rather than forcing the Kremlin to obey, they have been, if anything, marginalized even more, once again turning inwards, relying on no one but themselves––and their Ukrainian buffer.

When we look at a map, one of the first things that stand out are the carefully carved lines that make the borders of a state. The end of the Cold War has added many new lines and shapes to the map of Eastern Europe, but it has not added a new topographical alto-relief, indicating the mountains that Putin keeps praying for. The stretch between Moscow and the Atlantic Ocean remains dark green, and, most importantly, flat. This means that Russia has to rely on other means of creating a defense line––its immediate neighbours. So, when Bush announced the end of the Soviet Union, what he meant was the end of an ideology, rather than the end of geopolitical power struggles. And when he called Eastern Europe “free,” what he meant was: “As free as one can be when sandwiched between Russia and the rest of Europe.”

Related articles:

Ukraine: Revolution of Dignity

NATO Membership: Better Defence at a Lower Cost

Photo credits:

Sam Oxyak, Unsplash

Марьян Блан (@marjanblan), Unsplash

Jeroen, Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 3.0